“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau

“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau

The day after Thanksgiving. Sitting amidst my family last night, I had a sudden realization. I am no longer the center of anyone else’s life. My children grown, my parents gone, and Ted and I both, freed from the focus of raising kids have spun out from the center of family and are each pursuing our own questions and passions. What does this mean, to be freed from that kind of responsibility?The day after Thanksgiving. Sitting amidst my family last night, I had a sudden realization. I am no longer the center of anyone else’s life. My children grown, my parents gone, and Ted and I both, freed from the focus of raising kids have spun out from the center of family and are each pursuing our own questions and passions. What does this mean, to be freed from that kind of responsibility?

I look up from my list of have tos and must dos and watch what’s happening out the window. The antics of a squirrel as it leaps from the bouncing wand of the thinnest branch tips to the birdfeeder. Then a doe, unexpected in my garden, chewing the remains of the cabbage. A glance out the kitchen window reveals the two rabbits that have taken up residence in our mower shed, grazing on the still green grass. One is a deer brown, streaked and splotched with black, giving it a certain derelict air. The other a russet beauty with black tipped ears. With the relentless chores pulling at me to get something accomplished, I almost turn my back on these calls from the wild—but no—not this time.

I don boots and jacket and head to the backwoods. Rather than take my usual circuit, starting with the pond, I wind around the other way, following the rusty, tawny path of leaf litter. A red-tail circles overhead, checking me out. I watch his loops and dives and something flutters to my feet—a long thin feather striped cream and umber.

I make my way into the cushiony moss meadow, which I sometimes refer to as the dying place, since there have been several deer carcasses, and mounds of dove feathers from the hawk’s successful hunts. And yes, gleaming white against the incongruously spring green moss is the jawbone of faun.

Looking toward the river my eye is caught by the sun gold light shimmering on the hills through the cottonwood trunks, pressed between the steely blue of the far mountains and the river. With my eyes fixed on those two colors that speak November, I don’t notice the tips of the antlers sticking above the dry grass not 20’ in front of me. Not until the buck jerks awake, clearly as startled by my presence as I am by his. He rises, stands for just a moment before gracefully leaping the fence. He looks back at me as if to say, “Don’t you wish you could do that?” and then saunters away, secure in the knowledge I can’t.

The hawk circles overhead again. By the time I push my way through the willows to the water, the buck is nowhere to be seen. A heron startles off the bank across the water, it’s pterodactyl form outlined against the pinkening clouds

I find a perfect oval wishing rock, bigger than my palm, with a wide white band of quartz encircling it. As I am contemplating what to wish for, a splash erupts from the river right in front of me. Confused, I glance up to see the ring of water spreading from the center toward the spit where I stand. I look back down at my hand, which still holds the wishing rock. I scan the riverbank looking for someone else, but I am alone.

And then, downstream a small dark brown nose pops out of the water, then a little round head, a V of wake streaming behind. It must hear my delighted gasp, because its body humps up out current and its tail whacks the water , making another resounding splash as it dives below the surface. Walking downriver I watch as it rises and slaps, each time getting more distant until I can no longer see or hear it.

I could however hear the cacophonous sound of a huge flock of geese, doing their calligraphic flight formations, long stings of them flying back and forth, as if stitching the clouds together into a story.

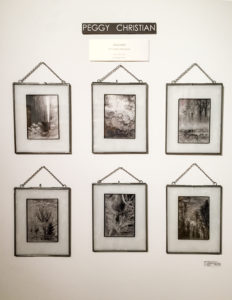

This. This is what I want. This time to “daily be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks!” Time to answer the call of the wild, and to stitch my experiences together with writing and photography.

I grasp the wishing rock in my hand, but instead of a wish, I whisper a commitment to myself. To take the freedom I now have from being the center of other people’s lives, and to become the center of my own life. To make my art, not something I do only in stolen moments, but the real focus of everything.

I throw the wishing rock far out to the center of the current and watch as it creates silvery rings which spread in all directions.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The last two weeks in Missoula have been unrelentingly cold with inversions trapping the valleys under a veil of dismal grey. For many people this has been trying–particularly since we are all breathlessly waiting for snow and the beginning of ski season. But the photographer in me has been rejoicing because the fact that the daytime temperatures never rise above the mid-20s means that the pond and riverbank have been an ever-changing landscape of ice. The fascinating forms captured by the freezing water are artworks far surpassing what my own imagination could ever conjure up.

The last two weeks in Missoula have been unrelentingly cold with inversions trapping the valleys under a veil of dismal grey. For many people this has been trying–particularly since we are all breathlessly waiting for snow and the beginning of ski season. But the photographer in me has been rejoicing because the fact that the daytime temperatures never rise above the mid-20s means that the pond and riverbank have been an ever-changing landscape of ice. The fascinating forms captured by the freezing water are artworks far surpassing what my own imagination could ever conjure up.

“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau

“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?

The morning after the election was a heartbreaking, confusing time for me. It was not just that my candidate had lost–that had happened before–or that the president elect would not agree with me on the issues that I consider most important. It was not even the possibility that this man might lead the country into another catastrophic war. That too had happened before. No–what devastated me was the fact that I could not understand how the electorate could vote for someone who so clearly had no moral or ethical center. Did that mean that half the country also lacks a moral and ethical center?