winter’s final blast

ski slopes haunted by ghosts

of season passing.

For centuries amateur naturalists have kept field notebooks. These are excerpts from my own nature journal–a hodge-podge of observations, bits of natural history, questions to ponder, insights and experiences.

winter’s final blast

ski slopes haunted by ghosts

of season passing.

In one of Elizabeth Strout’s stories in Olive, Again a character remarks on the quality of February light. “What she would have written about was the light in February. How it changed the way the world looked. People complained about February; it was cold and snowy and oftentimes wet and damp, and people were ready for spring. But for Cindy the light of the month had always been like a secret, and it remained a secret even now. Because in February the days were really getting longer and you could see, if you really looked. You could see how at the end of each day the world seemed cracked open and the extra light made its way across the stark trees, and promised.”

The promise of spring is all around if you look carefully, past the grey days and the occasional flurry of snow. One day you will walk past the same bank of willows and suddenly they seem to glow golden with an inner light and the red osier dogwoods flame a blood scarlet. The great horned owls who began calling back and forth in the twilight last month are already nesting. And beavers, coyotes and foxes are all mating. As are the hairy and downy woodpeckers and flickers whose drumming fills the morning quiet. Even the hardy little chickadees are practicing their mating calls.

The ground is scattered with wind blown seeds already softening in the wet snow, just waiting to drop down into the dirt and germinate. Even beneath the ragged snowcover, in the subnivean layer, voles who torment you in the summer garden are reproducing. And as more sunlight filters through, plants have begun to grow. Newly hatched stoneflies are crawling over the snow and in their dens mother bears have already given birth.

The ancient Celts recognized the beginning of spring, on the first of February, the Cross Quarter, half way between the Solstice and the Equinox. To them it was Imbolc or Brighid. For me, this light of February is a bittersweet light. I am reluctant to see the end of winter. Every new snowfall now is a celebration, a chance to savor for a few more days the quiet, contemplative beauty of a winter’s day. But these last snowfalls are fleeting, giving way to the slush and blue skies of longer days and warmer weather and all around me are the reminders of the changing seasons

I

Walking through the nearly snow-bare backwoods, I follow a dried overflow channel that snakes its way through the forest, from pond to the main river. In high spring runoff this channel is full, but now it provides an easy access to the river bank. Deer have created a way through the willows and soon I’m standing on the rocky spit. The end of January and there is no ice–the days have been in the high 30’s and 40’s, the nights staying too warm to freeze.

It is hard to believe that 24 years ago, nearly to the day, an ice jam on the Blackfoot river caused the scouring of the mine and smelter tailings that had accumulated behind the Milltown dam for the preceding 88 years and their release into the Clark Fork River. This was the pivotal event that lead to the Superfund removal of the dam and the 6.6 million cubic yards of toxic sediment behind it.

1996 was also the year of the flood when record amounts of snow melted and sent the water spilling over the banks, not only filling the old channels, but creating a virtual lake of the backwoods. Across the river was a newly built expensive house, right on a bend where another overflow channel used to be. The flood ate away a goodly portion of their front yard. Afterwards they got permission from the county to build a bend-away weir in the river bed, forcing the flood waters away from their house and into the backwoods. Then, over the years they have piled up a long wall of rip-rap so that now it appears the house sits on the edge of a small rocky cliff.

The river has seen many engineered changes, from the dam to irrigation projects, levies in the downtown to riverfront development that tries to control the water and force it into a designated and constricted course. But rivers are capricious as well as powerful and the last couple of flood years have nearly destroyed a small neighborhood where the river has changed course and created a new channel.

Now another engineer has moved into the neighborhood and begun work on the river. As I make my way back through the willows to where a small stand of new cottonwoods have taken root, my way is block by several toppled trees. The ground is littered with wood chips and the trunks riddled with tooth marks, The lack of snow and ice this winter has meant an extended season for their work. These engineers, however are more than welcome.

A few months ago I read a wonderful new book by Ben Goldfarb–Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. I then had the privilege of hearing him give a presentation at the Montana Natural History Center and I am now a confirmed “Beaver Believer.”

Goldfarb says, “Beavers are environmental Swiss Army knives, capable of tackling just about any ecological dilemma. Trying to slow down floods or filter out pollution? There’s a beaver for that. Hoping to capture more water for agriculture in the face of climate change? Add a beaver. Concerned about erosion, salmon runs, or wildfire? Take two beaver families, and check back in a year.” I can hardly wait to see what the beavers do to my short stretch of the river, and what they can teach me about engineering a future where, instead of dominating and trying to control nature, we humans can collaborate with other species to restore our natural ecosystems.

I have come to river’s edge to spend a few moments letting go of the day’s busyness, to try to quiet my scattered thoughts and worries. I sit on the wind swept trunk of an uprooted tree. An overnight freeze has sent hundreds of small rafts of ice into the river and I watch as they flow down the current, pass under the bridge and disappear around the snow-crusted sandbar. Slowly my thoughts drift away with them and I’m not aware of the cold seeping into my clothes as I sit entranced by the flotilla that appears like clouds scuttling through the reflected sky of water.

But the gathering of ice in an eddy near the shore draws me back. One by one frozen chunks are pulled out of the main current and swirl together, beginning to spin as they are sucked into the scour hole. As one after another attaches itself to the outer edges they coalesce and I am caught up in the growing crystalline spiral. It feels like magic, the way all the pieces are coming together, as if I am on the verge of a marvelous discovery.

But then the revolving circle begins to scrape along the rocks in the shallower water. The grinding sound gets louder as the blue water between the ice and the bank gets thinner and thinner until the ice sheet suddenly catches up on the shore and begins to shudder. The spinning slows, then stops as the ice distends and distorts, frozen in place and all that is left is a frigid spit. The free floating rafts of ice slip past to continue their journey downriver and I try to loose myself and drift downstream again with them, but now I am distracted by the cold and the spell is broken.

The great horned owls have begun their seasonal call and response—from cottonwoods to ponderosas, their haunting echoes through the backwoods just as the daylight is fading and darkness falls. The owls have been a constant throughout the last few years—their nesting sites down towards the river. I have watched as they roosted in the branches near the house. I awoke one morning to see two piercing yellow eyes staring at me from the tree outside my bedroom window. I have scavenged the ground for their pellets and pulled them apart to find skulls and pelvic bones and reconstructed the skeletons of whatever they had feasted on the last few days.

I even found a dead great horned that had been hit by a car. I took it to the natural history museum at the university and helped the curator prepare it as a teaching specimen. I parted the chest feathers to reveal the patch of soft bare skin where it nestled down on its eggs to warm them, I opened its stomach to reveal the partially digested dove it had consumed just before dying. And inside the dove, the seeds of its last meal.

I watched as an owl dove into the berry garden after a small bird that had wriggled its way into the sweet fruit through a gap in the fence. The owl glided in on silent wings, talons extended, but hit the netting over the garden, tumbled and rolled across the top and finally came to rest on a cross beam, feathers all askew and a confused look on its usually wise face. The little bird quietly hunkered under the blueberry bush, probably wondering at its brush with death.

I found one of my chickens decapitated in the yard—the victim of a great horned owl who is known to crave the brains of its prey. Many Native American cultures consider the owl an omen of death and I was uneasy when they became such an ever-present part of my life. And this year their calls do seem to echo with death. So many deaths of good friends and relations these last few years—my mother, my mother-in-law and my brother-in-law, a couple of Ted’s childhood friends. This fall our neighbor, a surrogate grandfather to my sons who never knew their grandfathers who passed many decades ago. And then, on New Year’s, the sudden death of our friend and the drummer in Ted’s band, Micki Singer, killed in a head-on accident on his way home from a gig. In spite of suffering for years from health problems, he was always eager to share his passion for music and never passed up an opportunity to play.

With no parents still alive and on social security, death seems so much closer than it ever has before. Our future no longer stretches in front of us, full of endless possibility. And yet, I don’t feel like the owls that are haunting me presage death. For I have also seen a pair of owls courting each other, watched as the male fluffed his white chest feathers, cocked his tail and bobbed and nodded, uttering “come hither” calls. I watched as the female spread her wings and bowed, snapping her bill. And then the male flew to her and they clacked beaks. Their calls were quick and urgent, he mounted her and it was over in just seconds.

Later that summer I found their nests and watched day after day as the awkward balls of fluff feathered out and finally fledged, learning to hunt on their own. Great horned owls are among the earliest species of birds to nest and their courting calls begin just as the solstice brings its promise of lengthening daylight and renewal. To hear them calling now reminds me that life and death are intertwined. But I learned from Micki that every day is a chance to do what you love and to not waste a moment of the life we have left.

The garden is put to bed, the pantry full of salsas, sauces, jams and relishes, and the freezer full of antelope, and Christmas come and gone. With the new year only a few days away, it is time for some quiet reflection on this past year—the experiences we harvested, the images preserved, not on film, but in pixels.

In January Candace and I sold the art center and I built (or I should say, Ted built) a little studio at home where I can look out on the backwoods as I work and avoid going into town for days at a time. I think of it as my exploritorium—a place where I can feed my curiosity, learn and spend even more time exploring in the woods.

And then last summer Ted and I embarked on a new journey, though in many ways it felt like a return to one of the best parts of our past. We became volunteer wilderness rangers in Glacier National Park. While Ted was a backcountry ranger 30years ago, first at Kintla Lake in the northwest corner of the park and then at Walton on the southern tip along the Middle Fork, this time we were stationed in a part of the park we had never gotten a chance to explore—the Belly River in the northeast corner. For a week or two every month from May through September we hiked the 6 miles in to the Belly River Ranger station and assisted the two full time rangers—Tracey Wiese and Bruce Carter—by patrolling the trails, checking campsites, talking to visitors and doing weed surveys and maintenance.

First of all, if you haven’t backpacked in 30 years it is quite a reckoning to realize that you just aren’t as young and fit as you used to be. Thankfully we were assigned a cabin to stay in so we didn’t have pack in a tent and all our cooking gear. We even got our food packed in once the station received their stock—two pack mules and a horse.

The Belly River is a many storied place and unique in its remoteness. Few visitors come to the Belly River—the limited number of campsites are by permit only the trailhead takes off from the Canadian border, a long mile drive from the nearest “tourist” destination of Many Glacier, so day hikers are a rare phenomena. We do get a lot of Continental Divide hikers on the last leg of their phenomenal 3,000 mile journey from the Mexican border, but they are a different breed from the typical tourist in Glacier. And we are looking forward to returning this summer to continue the adventure.

So, with my new home studio and a whole new world in the Belly River to explore in the coming year, I am restarting my blog as a way to reflect on and deepen my experiences in the natural world and to record whatever I may discover. I hope you’ll join me on my explorations and share whatever wonders you may find in the coming year.

The last two weeks in Missoula have been unrelentingly cold with inversions trapping the valleys under a veil of dismal grey. For many people this has been trying–particularly since we are all breathlessly waiting for snow and the beginning of ski season. But the photographer in me has been rejoicing because the fact that the daytime temperatures never rise above the mid-20s means that the pond and riverbank have been an ever-changing landscape of ice. The fascinating forms captured by the freezing water are artworks far surpassing what my own imagination could ever conjure up.

The last two weeks in Missoula have been unrelentingly cold with inversions trapping the valleys under a veil of dismal grey. For many people this has been trying–particularly since we are all breathlessly waiting for snow and the beginning of ski season. But the photographer in me has been rejoicing because the fact that the daytime temperatures never rise above the mid-20s means that the pond and riverbank have been an ever-changing landscape of ice. The fascinating forms captured by the freezing water are artworks far surpassing what my own imagination could ever conjure up.

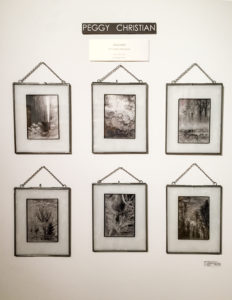

In a workshop at the Photographer’s Formulary with Dan Burkholder, I learned how to use precious metal leafing techniques with prints made on translucent velum. This creates a modern take on the famous orotones done by Edward S. Curtis in the 19th century west.

This technique is wonderfully suited to my series of icescapes. A selection of these silver leafed prints are in the current show at the Dana Gallery in Missoula, MT.

“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau

“Talk of mysteries—Think of our life in nature,–daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! The actual world! The common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? Where are we? H.D. Thoreau

The day after Thanksgiving. Sitting amidst my family last night, I had a sudden realization. I am no longer the center of anyone else’s life. My children grown, my parents gone, and Ted and I both, freed from the focus of raising kids have spun out from the center of family and are each pursuing our own questions and passions. What does this mean, to be freed from that kind of responsibility?The day after Thanksgiving. Sitting amidst my family last night, I had a sudden realization. I am no longer the center of anyone else’s life. My children grown, my parents gone, and Ted and I both, freed from the focus of raising kids have spun out from the center of family and are each pursuing our own questions and passions. What does this mean, to be freed from that kind of responsibility?

I look up from my list of have tos and must dos and watch what’s happening out the window. The antics of a squirrel as it leaps from the bouncing wand of the thinnest branch tips to the birdfeeder. Then a doe, unexpected in my garden, chewing the remains of the cabbage. A glance out the kitchen window reveals the two rabbits that have taken up residence in our mower shed, grazing on the still green grass. One is a deer brown, streaked and splotched with black, giving it a certain derelict air. The other a russet beauty with black tipped ears. With the relentless chores pulling at me to get something accomplished, I almost turn my back on these calls from the wild—but no—not this time.

I don boots and jacket and head to the backwoods. Rather than take my usual circuit, starting with the pond, I wind around the other way, following the rusty, tawny path of leaf litter. A red-tail circles overhead, checking me out. I watch his loops and dives and something flutters to my feet—a long thin feather striped cream and umber.

I make my way into the cushiony moss meadow, which I sometimes refer to as the dying place, since there have been several deer carcasses, and mounds of dove feathers from the hawk’s successful hunts. And yes, gleaming white against the incongruously spring green moss is the jawbone of faun.

Looking toward the river my eye is caught by the sun gold light shimmering on the hills through the cottonwood trunks, pressed between the steely blue of the far mountains and the river. With my eyes fixed on those two colors that speak November, I don’t notice the tips of the antlers sticking above the dry grass not 20’ in front of me. Not until the buck jerks awake, clearly as startled by my presence as I am by his. He rises, stands for just a moment before gracefully leaping the fence. He looks back at me as if to say, “Don’t you wish you could do that?” and then saunters away, secure in the knowledge I can’t.

The hawk circles overhead again. By the time I push my way through the willows to the water, the buck is nowhere to be seen. A heron startles off the bank across the water, it’s pterodactyl form outlined against the pinkening clouds

I find a perfect oval wishing rock, bigger than my palm, with a wide white band of quartz encircling it. As I am contemplating what to wish for, a splash erupts from the river right in front of me. Confused, I glance up to see the ring of water spreading from the center toward the spit where I stand. I look back down at my hand, which still holds the wishing rock. I scan the riverbank looking for someone else, but I am alone.

And then, downstream a small dark brown nose pops out of the water, then a little round head, a V of wake streaming behind. It must hear my delighted gasp, because its body humps up out current and its tail whacks the water , making another resounding splash as it dives below the surface. Walking downriver I watch as it rises and slaps, each time getting more distant until I can no longer see or hear it.

I could however hear the cacophonous sound of a huge flock of geese, doing their calligraphic flight formations, long stings of them flying back and forth, as if stitching the clouds together into a story.

This. This is what I want. This time to “daily be shown matter, to come in contact with it,–rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks!” Time to answer the call of the wild, and to stitch my experiences together with writing and photography.

I grasp the wishing rock in my hand, but instead of a wish, I whisper a commitment to myself. To take the freedom I now have from being the center of other people’s lives, and to become the center of my own life. To make my art, not something I do only in stolen moments, but the real focus of everything.

I throw the wishing rock far out to the center of the current and watch as it creates silvery rings which spread in all directions.

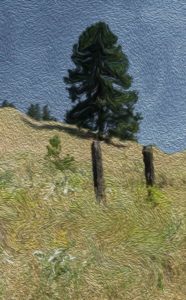

Last month the Dana Gallery in Missoula held their annual Paintout. Several local writers were invited to accompany the artists into the field and write in response to the scene. I was fortunate to join Robert Moore in the Lavelle Creek valley. The paintings and writings are on display at the gallery through August.

Begin with an underpainting. Great gravelly shores of a lake tens of thousands of years gone. Dusky grey with thin soils that lie heaped to the horizon line. Begin to sketch in the grasses whose network of roots hold that soil from gathering up into the winds that rake this slope.

Pull the individual stems from the plain brown hillside. Mix words on your palette to give definition to those grasses. Timothy and fescue, tawney and ecru, tufted hairgrass and sedge, raffia and buff. Struggle to give the right shape to your words so feathery seed heads come alive and dance on the page as they are shimmying now in the breeze. Look closer and see the greens that are woven into the tapestry. Sagey lupine heavy with furred pods and dusty verdigris balsam root drying in the searing sun. Try to capture the rustle of leaves and stems as some unseen creature darts among the safe cover of grasses, while overhead a feathered form sails across the clear blue sky.

Upslope, the burnt umber shadow of the single pine pools from its base and crawls uphill. How to render the ponderosa? Not spired like spruce or leggy like lodgepole. Words must spread in great boles and boughs, tufted with long needles. Pull the vanilla scent from the puzzled bark onto the page. Try to find the right values for your words. Suddenly the rock nestled at the foot of the ponderosa resolves itself into the hunched form of a wild turkey, escaping the midday sun.

Let the image of the turkey pull you into your own cool shade. Hunker yourself into the shadow of the serviceberry bush that softens the roadcut where you sit, dabbing letter into word into image.

You read the scene you have painted on the page. You like the way the colors mix and blend, the shading that has given it depth, and pulled you into the picture.

A branch dangles just above your eyes, heavy with small hard berries. Know they will ripen with time into something that will nourish you, the way all this foliage is transforming sunlight into life.